My way into KiKi Petrosino’s latest collection Witch Wifewas through the poem “Afterlife.” Thanks to this poem, I realized the book was about getting dumped. And dumped. And dumped. But also about rising above the heart carnage to transform hurt into a magical handbook for survival. Petrosino is a witch whose wand is language, and who waves it deftly to pronounce the transformational power of failed love. Her speaker is no maiden in distress, but a sorceress who feeds off each freshly and proudly acquired open wound.

So, in “Afterlife,” she asserts:

Petrosino’s speaker is indebted to none for her “healed mark.” Sure, it may have originated due to a lover’s sleight of hand, but that hand is long gone, now busy taking “golden hikes.” She claims ownership of this “mark” through her writing; each poem is a step in a ladder that leads away from loneliness and regret.

In “Break-Up-A-Thalamion” she roars:

“I don’t care / for your bakery smug. / I’m crying you out.”

In “Nocturne” she announces:

“It’s true that I love & that I do not love. / I fill myself with my regrets & begin to speak.”

It is true that we all love and that we all do not love. However, it is not true that we all are able to use heartbreak as a catalyst for speech. More often than not, heartbreak becomes a maker of mute suffering. But, Petrosino’s speaker is different. She is too deeply married to incantations to fall silent. It is precisely thanks to her “healed mark,” thanks to her exceptional loneliness, that she gains the insight she needs to see the world in a way that no one else can. And, so, the ability to render suffering into strength via language makes the witch. Petrosino is grateful to the past wounds by which she became a witch, so much so that she declares herself a “Witch Wife.” In other words, the poet weds solitude eagerly, seeing in this solitude the promise of poem.

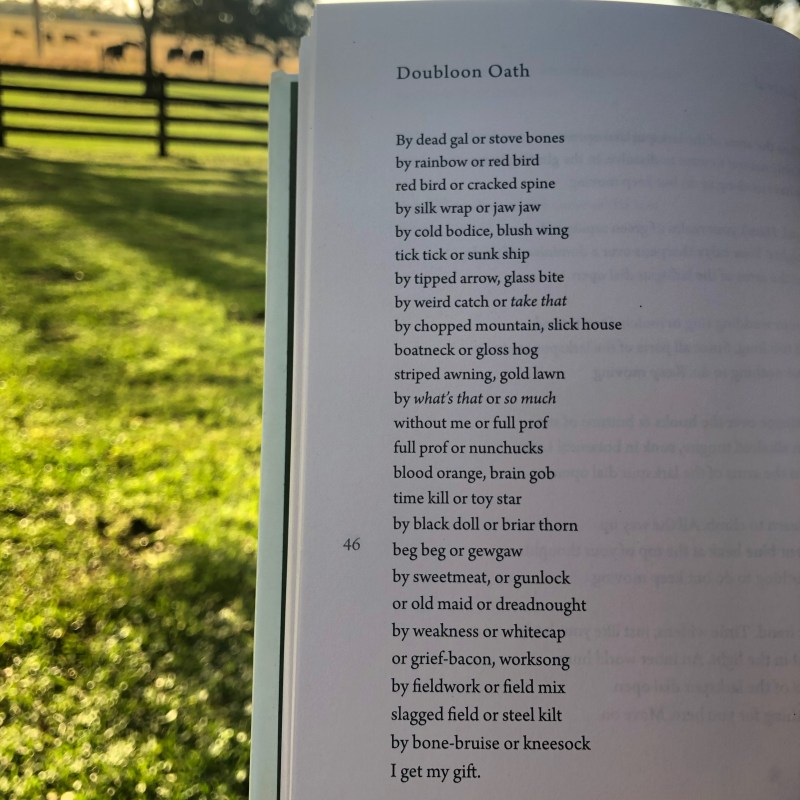

By all means, Petrosino is a powerful witch. Because of her sharp connection to spells, and their ingredients – words – she is able to rename the world around her, element by element, and, in doing so, she creates a new realm, one in which the poet dominates the landscape. Perhaps the poem that finds Petrosino’s sorcery at its best is “Doubloon Oath.” A “doubloon” is a Spanish Colonial coin, appropriated by pirates of yore as currency. In this piece, Petrosino loots language, sacking meaning from one word to give to the next, in order to overcome. It is such a delicious poem that it deserves to be reproduced in its entirety. So, here it is:

There is no sorrow when one controls the elements. Witches know this. Whatever they lack, they can conjure. And how? By knowing and by saying. In the book’s title poem “Witch Wife,” Petrosino’s speaker describes how this is done:

“I conjure with my pink-and-green gloves

wrangling life from the dirt. It all turns out

as I’d hoped.”

In the world the witch conjures, the outcomes are controlled; they satisfy hope. The conjured world is a good world, one to which not all have access. And access comes by way of intimate, diligent knowledge of love lost. Why diligent? Because to gain from loss the poet must value it, must use it, must store it. This is hard work.

What’s more: to sing of loss the poet must forever remain “All alone, all alone, all alone, all alone,” as alone as the object of Petrosino’s poem “Voice Lesson.” In it a rakish narrator speaks to a “Bird of Paradise.” According to the narrator, the bird is at once alone and “not made for onliness”(sic). Also according to the narrator, the bird, an evident avatar for Petrosino, must make a choice: either be pretty or sing.

As tempting as it is to be a “pretty mouth,” Petrosino, the witch, must sing. And sing, and sing. She needs to work her magic, her verse. Sorrow is not possible. No, she is too powerful to be sad. But in her might, she is alone. The poet/bird remains alone. In her loneliness, her mighty loneliness, she can conjure new elements, but she realizes that to fully evolve she must also concede to the maker of the world as is. Petrosino is a good witch, one who understands she still has much to learn, one who understands that ultimately she needs to love.

Her closing poem, “Purgatorio,” ends the book in a place of transition, in purgatory, between the hell of heartache and the heaven of fulfillment. In the end, the wonder of the wooded world is not enough for the witch. She still seeks love, and so the witch must bow her head and pray: